Without collapsing critical thinking into relativism, hermeneutics recognizes the historicity of human understanding. Ideas are nested in historical, linguistic, and cultural horizons of meaning. A philosophical, theological, or literary problem can only be genuinely understood through a grasp of its origin. Hermeneutics is in part the practice of historical retrieval, the re-construction of the historical context of scientific and literary works. Hermeneutics does not re-construct the past for its own sake; it always seeks to understand the particular way a problem engages the present. A philosophical impulse motivates hermeneutic re-construction, a desire to engage a historically transmitted question as a genuine question, worthy of consideration in its own right. By addressing questions within ever-new horizons, hermeneutic understanding strives to break through the limitations of a particular world-view to the matter that calls to thinking.

About Hermeneutics

definition: Hermeneutics may be described as the theory of interpretation and understanding of the text through empirical means. It should not be confused with the concrete practice of interpretation called exegesis. Exegesis extracts the meaning of a passage of text and enlarges upon it and explicates it with explanatory glosses; hermeneutics addresses the ways in which a reader may come to the broadest understanding of the creator of text and his relation to his audiences, both local and over time, within the constraints of culture and history. Thus it is a branch of philosophy concerned with human understanding and the interpretation of texts....

Wikipedia

...a clear understanding?

28 September 2005

27 September 2005

the sky is falling, the sky is falling...

25 September 2005

imagination, thought, ideas...

23. But, say you, surely there is nothing easier than for me to imagine trees, for instance, in a park, or books existing in a closet, and nobody by to perceive them. I answer, you may so, there is no difficulty in it; but what is all this, I beseech you, more than framing in your mind certain ideas which you call books and trees, and the same time omitting to frame the idea of any one that may perceive them? But do not you yourself perceive or think of them all the while? This therefore is nothing to the purpose; it only shews you have the power of imagining or forming ideas in your mind: but it does not shew that you can conceive it possible the objects of your thought may exist without the mind. To make out this, it is necessary that you conceive them existing unconceived or unthought of, which is a manifest repugnancy. When we do our utmost to conceive the existence of external bodies, we are all the while only contemplating our own ideas. But the mind taking no notice of itself, is deluded to think it can and does conceive bodies existing unthought of or without the mind, though at the same time they are apprehended by or exist in itself. A little attention will discover to any one the truth and evidence of what is here said, and make it unnecessary to insist on any other proofs against the existence of material substance.

A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge, George Berkeley, 1710

...and what of things that we don't know that we don't know?

A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge, George Berkeley, 1710

...and what of things that we don't know that we don't know?

22 September 2005

arts, science, design...

Among the branches of philosophy, I had, at an earlier period, given some attention to logic, and among those of the mathematics to geometrical analysis and algebra, -- three arts or sciences which ought, as I conceived, to contribute something to my design. But, on examination, I found that, as for logic, its syllogisms and the majority of its other precepts are of avail- rather in the communication of what we already know, or even as the art of Lully, in speaking without judgment of things of which we are ignorant, than in the investigation of the unknown; and although this science contains indeed a number of correct and very excellent precepts, there are, nevertheless, so many others, and these either injurious or superfluous, mingled with the former, that it is almost quite as difficult to effect a severance of the true from the false as it is to extract a Diana or a Minerva from a rough block of marble. Then as to the analysis of the ancients and the algebra of the moderns, besides that they embrace only matters highly abstract, and, to appearance, of no use, the former is so exclusively restricted to the consideration of figures, that it can exercise the understanding only on condition of greatly fatiguing the imagination; and, in the latter, there is so complete a subjection to certain rules and formulas, that there results an art full of confusion and obscurity calculated to embarrass, instead of a science fitted to cultivate the mind. By these considerations I was induced to seek some other method which would comprise the advantages of the three and be exempt from their defects. And as a multitude of laws often only hampers justice, so that a state is best governed when, with few laws, these are rigidly administered; in like manner, instead of the great number of precepts of which logic is composed, I believed that the four following would prove perfectly sufficient for me, provided I took the firm and unwavering resolution never in a single instance to fail in observing them.

The first was never to accept anything for true which I did not clearly know to be such; that is to say, carefully to avoid precipitancy and prejudice, and to comprise nothing more in my judgement than what was presented to my mind so clearly and distinctly as to exclude all ground of doubt.

The second, to divide each of the difficulties under examination into as many parts as possible, and as might be necessary for its adequate solution.

The third, to conduct my thoughts in such order that, by commencing with objects the simplest and easiest to know, I might ascend by little and little, and, as it were, step by step, to the knowledge of the more complex; assigning in thought a certain order even to those objects which in their own nature do not stand in a relation of antecedence and sequence.

And the last, in every case to make enumerations so complete, and reviews so general, that I might be assured that nothing was omitted.

"The First Principle of Philosophy," Rene Descartes, Discourse on Method

...cogito ergo sum?

The first was never to accept anything for true which I did not clearly know to be such; that is to say, carefully to avoid precipitancy and prejudice, and to comprise nothing more in my judgement than what was presented to my mind so clearly and distinctly as to exclude all ground of doubt.

The second, to divide each of the difficulties under examination into as many parts as possible, and as might be necessary for its adequate solution.

The third, to conduct my thoughts in such order that, by commencing with objects the simplest and easiest to know, I might ascend by little and little, and, as it were, step by step, to the knowledge of the more complex; assigning in thought a certain order even to those objects which in their own nature do not stand in a relation of antecedence and sequence.

And the last, in every case to make enumerations so complete, and reviews so general, that I might be assured that nothing was omitted.

"The First Principle of Philosophy," Rene Descartes, Discourse on Method

...cogito ergo sum?

21 September 2005

Rule IV...

In experimental philosophy we are to look upon propositions collected by general induction from phænomena as accurately or very nearly true, notwithstanding any contrary hypotheses that may be imagined, till such time as other phænomena occur, by which they may either be made more accurate, or liable to exceptions.

This rule we must follow, that the argument of induction may not be evaded by hypotheses.

"Rules of Reasoning in Philosophy," Isaac Newton, Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy

..."rule" or "procedure?"

This rule we must follow, that the argument of induction may not be evaded by hypotheses.

"Rules of Reasoning in Philosophy," Isaac Newton, Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy

..."rule" or "procedure?"

14 September 2005

blue, uncertain, stumbling buzz...

I heard a fly buzz when I died;

The stillness round my form

Was like the stillness in the air

Between the heaves of storm.

The eyes beside had wrung them dry,

And breaths were gathering sure

For that last onset, when the king

Be witnessed in his power.

I willed my keepsakes, signed away

What portion of me I

Could make assignable, - and then

There interposed a fly,

With blue, uncertain, stumbling buzz,

Between the light and me;

And then the windows failed, and then

I could not see to see.

Emily Dickinson

...is death the only time we cannot see to see?

The stillness round my form

Was like the stillness in the air

Between the heaves of storm.

The eyes beside had wrung them dry,

And breaths were gathering sure

For that last onset, when the king

Be witnessed in his power.

I willed my keepsakes, signed away

What portion of me I

Could make assignable, - and then

There interposed a fly,

With blue, uncertain, stumbling buzz,

Between the light and me;

And then the windows failed, and then

I could not see to see.

Emily Dickinson

...is death the only time we cannot see to see?

13 September 2005

reason of an age...

You may have an opinion that a man is inspired, but you cannot prove it, nor can you have any proof of it yourself, because you cannot see into his mind in order to know how he comes by his thoughts; and the same is the case with the word revelation. There can be no evidence of such a thing, for you can no more prove revelation than you can prove what another man dreams of, neither can he prove it himself.

A Letter to a Friend Regarding the Age of Reason, Thomas Paine, Paris, May 12, 1797

...and to prove oneself?

A Letter to a Friend Regarding the Age of Reason, Thomas Paine, Paris, May 12, 1797

...and to prove oneself?

12 September 2005

the aggregates of existence...

"This again, indeed, O mendicants, is the noble truth of suffering. Birth is painful, old age is painful, sickness is painful, association with unloved objects is painful, separation from loved objects is painful, the desire which one does not obtain, this is too painful - in short, the five elements of attachment to existence are painful. The five elements of attachment to earthly existence are form, sensation, perception, components and consciousness.

Buddha, The Dahmmapada

...in pain is found truth?

Buddha, The Dahmmapada

...in pain is found truth?

11 September 2005

vacuity...

Form is emptiness, and the very emptiness is form; emptiness does not differ from form, form does not differ from emptiness; whatever is form, that is emptiness; whatever is emptiness, that is form. The same is true of feelings, perceptions, impulses and consciousness.

Diamond Sutra, Buddha

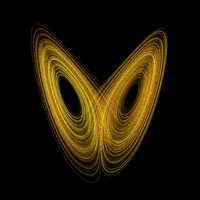

As in the Buddhist Diamond Sutra, chaos can be found in order, and order in chaos. The organizing principle is the key. The organizing principle used in Systemic Solutions is an experience of integrity - a stable experience of connectedness, integration and purpose - an experience of self-as-system that does not diminish with passing time.

Chaos & Consciousness

...being = existence; nothingness = absence of existence?

Diamond Sutra, Buddha

As in the Buddhist Diamond Sutra, chaos can be found in order, and order in chaos. The organizing principle is the key. The organizing principle used in Systemic Solutions is an experience of integrity - a stable experience of connectedness, integration and purpose - an experience of self-as-system that does not diminish with passing time.

Chaos & Consciousness

...being = existence; nothingness = absence of existence?

10 September 2005

chaotic tao...

Chaos is the supreme ideal of Taoism. Chaos is wholeness, oneness and Nature. Chaos represents the natural state of the world. Digging holes on the head of Chaos means destroying the natural state of the cosmos. Therefore, to the ancient Chinese people chaos not only has the meaning of disorder but also presents a respectable aesthetic state.

A Brief History of the Concept of Chaos Huajie Liu

A Brief History of the Concept of Chaos Huajie Liu

09 September 2005

浑沌

The ruler of the Southern Sea is called Change; the ruler of the Northern Sea is called Uncertainty, and the ruler of the Centre is called Primitivity(浑沌). Change and Uncertainty often met on the territory of Primitivity, and being always well treated by him, determined to repay his kindness. They said: "All men have seven holes for seeing, hearing, eating, and breathing. Primitivity alone has none of these. Let us try to bore some for him." So every day they bored one hole; but on the seventh day Primitivity died.

a chaos fable excerpted from one of the ancient Chinese classics Chuang-Tzu:《庄子》A New Seleted Translation with an Exposition of the Philosophy of Kuo Hsiang by Fung Yu-Lan (冯友兰)

...创 世 纪 (Genesis), 2:2 到第七日、 神造物的工已经完毕、就在第七日歇了他一切的工、安息了。

...and on the seventh day God ended his work which he had made; and he rested on the seventh day from all his work which he had made.

The Book of Genesis, 2:2

a chaos fable excerpted from one of the ancient Chinese classics Chuang-Tzu:《庄子》A New Seleted Translation with an Exposition of the Philosophy of Kuo Hsiang by Fung Yu-Lan (冯友兰)

...创 世 纪 (Genesis), 2:2 到第七日、 神造物的工已经完毕、就在第七日歇了他一切的工、安息了。

...and on the seventh day God ended his work which he had made; and he rested on the seventh day from all his work which he had made.

The Book of Genesis, 2:2

07 September 2005

a picture of chaos...?

The Lorenz attractor, introduced by Edward Lorenz in 1963, is a non-linear three-dimensional deterministic dynamical system derived from the simplified equations of convection rolls arising in the dynamical equations of the atmosphere. For a certain set of parameters the system exhibits chaotic behavior and displays what is today called a strange attractor....

Lorenz attractor

...strange can be breathtaking!

06 September 2005

predictablility...

"In science as in life, it is well known that a chain of events can have a point of crisis that could magnify small changes. But chaos meant that such points were everywhere. They were pervasive." (24)

John von Neumann

...small changes = ?

John von Neumann

...small changes = ?

05 September 2005

intentionality...

The Object Theory

The example of the imagining a centaur is famous in the history of philosophy. The object theory, and the difficulities surrounding it, derive from philosophical reflection on this and similar examples of the use of our imagination.

Certainly, in one sense, there exists an object in our imagination; the object must be "real" or we would not be able to imagine it. There is a picture of something in my mind.

On the other hand, the centaur is known to be a mythical being and hence has no existence. Is my thought, then, actually directed toward a non-existing object? How can this be if an intentional act requires an object? Surely, the object toward which my thought is directed exists, otherwise, if the object theory is correct, there would be no thought at all....

The Content Theory

The content theory seeks to resolve some of the difficulties of the object theory. It utilizes the idea that there must be an intermediary between consciousness and its ultimate object. For a first approximation, this intermediary can be variously called a "sign," a "representation," a "vehicle" or, more generically, a "content" in the intentional act. Thus, the act of thinking of imagining an actually existing thing (say, a table) is easily described and explained: my image of the table is the vehicle, while the object of my intention is the table itself. To solve the problem of non-existing beings that can be the objects of thought, the content theory allows that content can exist or "be" without the corresponding object. In imagining a centaur, I have a mental image whose content is a centaur. The centaur "exists" as content in my mind, but there is no object outside of the mind corresponding to this thought.

Difficulties for the Theory of Intentionality, Anthony Birch

...nothingness ≥ or ≤ ideas?

The example of the imagining a centaur is famous in the history of philosophy. The object theory, and the difficulities surrounding it, derive from philosophical reflection on this and similar examples of the use of our imagination.

Certainly, in one sense, there exists an object in our imagination; the object must be "real" or we would not be able to imagine it. There is a picture of something in my mind.

On the other hand, the centaur is known to be a mythical being and hence has no existence. Is my thought, then, actually directed toward a non-existing object? How can this be if an intentional act requires an object? Surely, the object toward which my thought is directed exists, otherwise, if the object theory is correct, there would be no thought at all....

The Content Theory

The content theory seeks to resolve some of the difficulties of the object theory. It utilizes the idea that there must be an intermediary between consciousness and its ultimate object. For a first approximation, this intermediary can be variously called a "sign," a "representation," a "vehicle" or, more generically, a "content" in the intentional act. Thus, the act of thinking of imagining an actually existing thing (say, a table) is easily described and explained: my image of the table is the vehicle, while the object of my intention is the table itself. To solve the problem of non-existing beings that can be the objects of thought, the content theory allows that content can exist or "be" without the corresponding object. In imagining a centaur, I have a mental image whose content is a centaur. The centaur "exists" as content in my mind, but there is no object outside of the mind corresponding to this thought.

Difficulties for the Theory of Intentionality, Anthony Birch

...nothingness ≥ or ≤ ideas?

and yet another cunundrum...

But may not the ideas, asked Socrates, be thoughts only, and have no proper existence except in our minds, Parmenides? For in that case each idea may still be one, and not experience this infinite multiplication.

And can there be individual thoughts which are thoughts of nothing?

Impossible, he said.

The thought must be of something?

Yes.

Of something which is or which is not?

Of something which is.

Must it not be of a single something, which the thought recognizes as attaching to all, being a single form or nature?

Yes.

And will not the something which is apprehended as one and the same in all, be an idea?

From that, again, there is no escape.

Then, said Parmenides, if you say that everything else participates in the ideas, must you not say either that everything is made up of thoughts, and that all things think; or that they are thoughts but have no thought?

The latter view, Parmenides, is no more rational than the previous one. In my opinion, the ideas are, as it were, patterns fixed in nature, and other things are like them, and resemblances of them-what is meant by the participation of other things in the ideas, is really assimilation to them.

But if, said he, the individual is like the idea, must not the idea also be like the individual, in so far as the individual is a resemblance of the idea? That which is like, cannot be conceived of as other than the like of like.

Impossible.

And when two things are alike, must they not partake of the same idea?

They must.

And will not that of which the two partake, and which makes them alike, be the idea itself?

Certainly.

Then the idea cannot be like the individual, or the individual like the idea; for if they are alike, some further idea of likeness will always be coming to light, and if that be like anything else, another; and new ideas will be always arising, if the idea resembles that which partakes of it?

Parmenides, Plato, 370 B.C.E.

...ideas = something?

And can there be individual thoughts which are thoughts of nothing?

Impossible, he said.

The thought must be of something?

Yes.

Of something which is or which is not?

Of something which is.

Must it not be of a single something, which the thought recognizes as attaching to all, being a single form or nature?

Yes.

And will not the something which is apprehended as one and the same in all, be an idea?

From that, again, there is no escape.

Then, said Parmenides, if you say that everything else participates in the ideas, must you not say either that everything is made up of thoughts, and that all things think; or that they are thoughts but have no thought?

The latter view, Parmenides, is no more rational than the previous one. In my opinion, the ideas are, as it were, patterns fixed in nature, and other things are like them, and resemblances of them-what is meant by the participation of other things in the ideas, is really assimilation to them.

But if, said he, the individual is like the idea, must not the idea also be like the individual, in so far as the individual is a resemblance of the idea? That which is like, cannot be conceived of as other than the like of like.

Impossible.

And when two things are alike, must they not partake of the same idea?

They must.

And will not that of which the two partake, and which makes them alike, be the idea itself?

Certainly.

Then the idea cannot be like the individual, or the individual like the idea; for if they are alike, some further idea of likeness will always be coming to light, and if that be like anything else, another; and new ideas will be always arising, if the idea resembles that which partakes of it?

Parmenides, Plato, 370 B.C.E.

...ideas = something?

04 September 2005

hopelessness...

The question looms in moments of great despair, when things tend to lose all their weight and all meaning becomes obscured....It is present in moments of rejoicing, when all things around us are transfigured and seem to be there for the first time, as if it might be easier to think they are not than to understand that they are and are as are. The question is upon us in boredom, when we are equally removed from despair and joy, and everything about us seems so hopelessly commonplace that we no longer care whether anything is or is not...

Martin Heidegger

... nothingness = despair?

Martin Heidegger

... nothingness = despair?

03 September 2005

a noiseless patient spider...

A noiseless patient spider,

I marked where on a little promontory it stood isolated,

Marked how to explore the vacant, vast surrounding,

It launched forth filament, filament, filament, out of itself.

Ever unreeling them, ever tirelessly speeding them.

And you O my soul where you stand,

Surrounded, detached, in measureless oceans of space,

Ceaselessly musing, venturing, throwing, seeking the spheres to connect them.

Till the bridge you will need be formed, till the ductile anchor hold,

Till the gossamer thread you fling catch somewhere, O my soul.

Walt Whitman

...to get from there to where?

I marked where on a little promontory it stood isolated,

Marked how to explore the vacant, vast surrounding,

It launched forth filament, filament, filament, out of itself.

Ever unreeling them, ever tirelessly speeding them.

And you O my soul where you stand,

Surrounded, detached, in measureless oceans of space,

Ceaselessly musing, venturing, throwing, seeking the spheres to connect them.

Till the bridge you will need be formed, till the ductile anchor hold,

Till the gossamer thread you fling catch somewhere, O my soul.

Walt Whitman

...to get from there to where?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)